Roosevelt’s Brew Deal

LA Got Over Its ‘Dry’ Spell 88 Years Ago

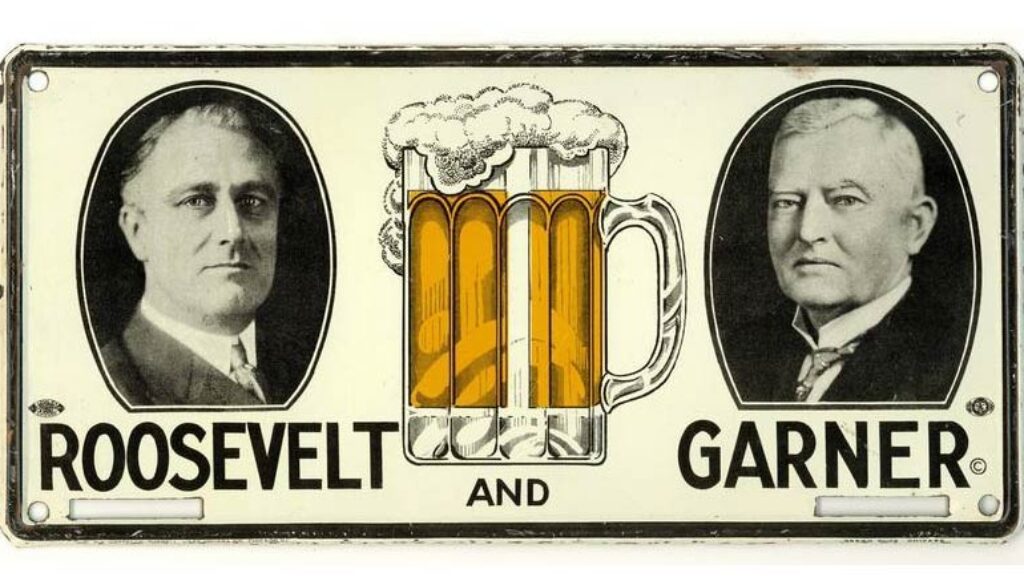

“I think this would be a good time for a beer.”

While this sounds like an appropriate declaration to make right now, as pandemic restrictions continue to lift and Southern California breweries and taprooms move closer to normal operations, it’s actually a quote from our 32nd President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Speaking on March 22, 1933, less than three weeks after his inauguration, FDR made good on his campaign pledge to repeal Prohibition as he signed into law that day the Cullen-Harrison Act (also known as the Beer-Wine Revenue Act), which was the first step toward fulfilling that promise. The law legalized, and taxed, beverages containing no more than 3.2% alcohol by weight (4.0% by volume), which the authors of the new bill were careful to define as “non-intoxicating”; these beverages were previously illegal for consumption in the US since the Volstead Act (aka the 18th Amendment) became law as of January 17, 1920. Under Prohibition, only beverages with 0.5% abv (0.4% abw) alcohol were allowed without a prescription.

(Why Volstead measured in abv, while Cullen-Harrison used abw has never been explained…maybe because abw sounds lower?)

Courtesy of SlidePlayer.com

The Cullen-Harrison Act required that states had to pass their own similar legislation to legalize sale of low-alcohol beverages within their borders, and for those that did, the new law took effect April 7, 1933. Nineteen states had passed such laws, California among them. Eight months later, on December 5, 1933, the Volstead Act was repealed by the 21st Amendment, legalizing full-strength alcohol. This date is known as Repeal Day.

But since 2009, April 7 has been celebrated as National Beer Day in the US, thanks to Justin Smith, a beer aficionado in Virginia, who started a Facebook page to commemorate it. The Untappd app then created a badge for National Beer Day and it began to catch on through social media. In 2017, National Beer Day was officially recognized in the Congressional Record.

As we commemorate this deserved hop-fueled holiday in SoCal in 2021, let’s take a look back at how Los Angeles breweries observed this liberating date 88 years ago, when, like today, a long, national nightmare was coming to an end…

When Prohibition took effect in early 1920, not long after the end of World War I, during the final throes of the H1N1 virus pandemic, and less than a decade before the Great Depression (talk about a string of bad luck!), the city of Los Angeles, with a population of some 570,000, only had three breweries in operation: Maier Brewing, Mathie Brewing and Los Angeles Brewing.

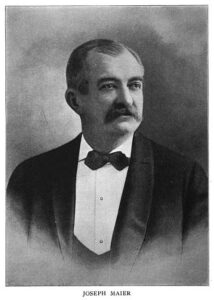

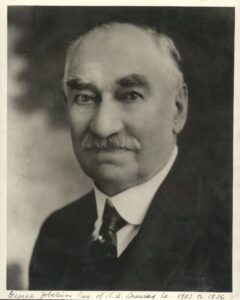

Courtesy of CemeteryGuide.com

The Maier Brewery, located at 95 Aliso Street (now an on–ramp for the 101 Freeway) was previously the Maier & Zobelein Brewery (1882-1907) and before that the Philadelphia Brewery (1874-1882), and originally the El Aliso Winery (1831-1862). It was LA’s oldest existing brewery at the time. Joseph Maier, the namesake co-founder, died of heart disease at 53 in 1905 and left his share of the business to his sons, Fred, who became president, and Edward Maier.

The Mathie Brewery, located at 1850 North Main Street (currently the site of a UPS Customer Center) was originally the Ferdinand A. Heim Brewery, founded in 1901 by, and named for, the nephew and heir to the late Ferdinand Heim, Sr., a brewing magnate from Kansas City. The younger Heim originally ran a bottling and distribution business on Ramirez Street. In 1903, Heim sold the brewery to Edward Mathie, who enlarged the facility and began operating in 1905. It was located literally across the street (Moulton Avenue) from Mathie’s previous place of employment…

Courtesy of CemeteryGuide.com

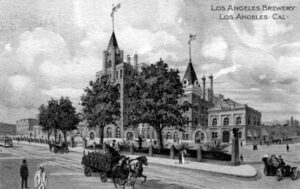

…the Los Angeles Brewery, which he co-founded with P. Max Kuehnrich in 1897 at 1920 North Main Street (now the Brewery Arts Colony in Lincoln Heights). Kuehnrich was president and general manager, with Mathie serving as vice president and superintendent. In 1902, a dispute between the principals over the financial mismanagement of the company resulted in Mathie trying to have Kuehnrich ousted, but the board of directors sided with the president, and Mathie himself was removed from the organization. The following year, he purchased the nearby Heim brewery.

Another clash of owners erupted back on Aliso Street when George Zobelein sued his recently deceased partner’s sons at Maier & Zobelein over company stock shenanigans once they owned half of the brewery. His suit was successful, and the Maier brothers bought Zobelein out for $500,000. With his settlement, he purchased the Los Angeles Brewery in 1907 from Kuehnrich. He named his newly brewed brand of beers “Eastside,” as the brewery was located East of the pre-concrete Los Angeles River.

Courtesy of Water and Power Associates

As Prohibition Grew Near, So Did the Beer

With the dawn of Prohibition looming closer on the horizon, no brewery owner was happy, obviously. On January 17, 1919 (exactly one year before the Volstead act would take effect), the Los Angeles Herald published an article gaging reactions of Angelenos to the imminent “Dry LA.” “This means the most terrible disaster for business,” brewery owner Mathie told the reporter. “In securing prohibition, the reformers have put thousands of people out of work, and ruined millions of dollars’ worth of business. In Los Angeles alone, about $2 million is affected just in the breweries. It is plain calamity.”

When the country did go “dry,” at least officially, most breweries in the nation transitioned into producing root beer and soft drinks, fruit juices, unfermented apple cider, even ice cream, as well as the legal 0.5% abv “near beer,” all to varying degrees of success, to stay in business. Some also made denatured alcohol.

Courtesy of the collection of Richard Foss

Los Angeles Brewing, which changed its name to Zesto Beverage Co. during the “dry” years, would also make regular Eastside beer, but removed the alcohol and provided that alcohol to industrial companies making paint or dye. Alcohol was also sold to the medical market (hospitals, doctors, dentists, drug stores) under the name Tru-Grain. The sale of these products enabled the brewery to keep pace with pre-Prohibition sales, according to the “Zobelein Family History,” compiled by Guilii Zobelein on Zobelein.com, which also claims that prior to 1920, Los Angeles Brewing Company was the fifth largest beer producer in the US. Not surprisingly, the brewery survived Prohibition intact.

Several US breweries, however, felt they could not, or did not want to, exist producing only near beer or the other sanctioned alternatives, and out of desperation, or defiance, continued to brew full-strength beer illegally, to surreptitiously supply the growing number of “speakeasies” — hidden, secret saloons that served liquor. (In fact, it has been said that at one point during Prohibition, there were more speakeasies in LA than there had been saloons before 1920!)

While some Volstead-violators undoubtedly got away with it, one such brewery that did not was Maier Brewing. On March 30, 1932 (ironically, just over a year before the production and sale of 4.0% abv beer was made legal), “a spectacular raid was staged by ten Prohibition agents on the plant of Maier Brewing Company,” reported the May 1932 issue of the journal The American Brewer. “The brewery and bottling plant, and all of their contents, valued at $3 million, were seized…” and the sales manager and another employee were arrested. “This is the first instance where a brewery operating under Government permit to make near beer has been padlocked on the Pacific Coast,” the article added.

Courtesy of the collection of Richard Foss

Despite the denial of then president (as his brother had died in 1909) Edward Maier of any knowledge about the illicit brew, the Feds claimed they had discovered “unshakable evidence” of the violation, according to “From Eastside Lager to Maier’s Select Malt Tonic: A Brief History of LA Beer,” a 2011 article by Nathan Masters on KCET.org.

Another blurb in the same issue of The American Brewer reported that the Maier bottling plant “had just been leased by owner Edward Maier to parties who were to enter into an extensive sales program for selling Cereal Beverages [Prohibition-era euphemism for near beer].”

The brewery reopened in May 1932 under a $10,000 federal bond, with its operations limited to “the movement of manufactured [legal] product on hand,” the July issue of The American Brewer wrote, also revealing that petitions in involuntary bankruptcy were filed in mid-June against Maier and his company. In June, Maier Brewing was forced into bankruptcy by creditors and put into a court-appointed receivership, but did not resume brewing until after Prohibition was repealed.

It wasn’t until 1940 that Maier finally regained control of his brewery in a court settlement — seven years after Prohibition ended. But tragically, he perished in a house fire three years later. Although it was never again family-owned, Maier Brewing eventually regained its status as one of LA’s biggest breweries over the years, and was responsible for the (in)famous Brew 102 in the 1950s. The company existed into the early 1970s before being renamed General Brewing, and then fading away.

Courtesy of the collection of Richard Foss

Confirming the aforementioned fears of its owner, as quoted in the Los Angeles Herald, Mathie Brewing was out of the brewing business even before January 17, 1920, when Prohibition took effect. That month, advertisements began appearing in the Herald hawking apple cider from Watsonville, California for delivery, and recommending “Serve Cider — the 1920 Beverage — for Health.” The cider was “stored in glass enamel-lined steel tanks” — the same ones Mathie had bragged about installing in articles and ads when he built out his brewery. The ads were for “Atlas Beverage Co. (formerly Mathie Brewery),” apparently a bottling plant and local distributor.

On June 23, the Herald ran an article announcing that one of the warehouses at the brewery would be used for preserving and dehydrating fruits and vegetables, as well as making by-products from them.

Then, in the February 18, 1921 edition of the San Pedro Daily News, an article announced that Mathie and his company’s board of directors had decided “the plant should be sold for the best possible price and at the earliest opportunity.” The newspaper added, “When Mr. Mathie was first asked [before the Volstead Act went into effect] what was to be done with the plant, he said he guessed he’d dedicate it to the prohibition element of the country…” Hence, the soft cider company.

Courtesy of the collection of Richard Foss

By late March, the brewery was sold to the Imperial Cotton Mills Company of Los Angeles, to be converted into a 20,000-spindle textile mill. That spring, Mathie was selling those glass enamel-lined steel tanks, the brewhouse, bottling line and other equipment in Herald classified ads, and in October, harvest season, classified ads ran to sell the brewery’s trucks for hauling grapes.

The Mathie Brewing property did become a brewery once again, however — after Repeal. San Diego’s Balboa Brewery purchased the facility as its second location in 1934, according to a 2018 article in West Coaster by Sheldon Kaplan entitled “A Look Back: San Diego Beer History from 1868 to 1953,” then changed its name to Monarch Brewing in 1936, but went out of business in 1942.

Mathie himself eventually returned to brewing as well. In the November 1935 issue of The American Brewer, it was announced that he had become the brewmaster at Lynwood Brewery in Los Angeles County.

Last Brewery Standing

Courtesy of the California Historical Society Collection, USC Libraries

The only LA brewery still in operation come April 7, 1933, Zobelein’s Los Angeles Brewing retired the Zesto Beverage name, and now was also known as Eastside Brewing. The whole state of California had only six breweries that were capable of producing “non-intoxicating” 4.0% abv beer by that date: three in San Francisco, one in Oakland, one in Stockton, and Eastside here in LA. Part of the reason was that the government gave breweries just over two weeks notice of the date that real beer would be no longer be illegal.

But Zobelein was in good shape, and ready to restart his old business immediately. Because Eastside was already brewing real beer, only removing the alcohol, all that was required was to bypass the denaturing process. According to Zobelein.com, as well as a March 2005 article on RustyCans.com, a beer can collecting website, “Numerous trucks were parked at the brewery, loaded and ready to go as the day when legal beer could be shipped approached… [E]ach truck was filled with bottles and barrels of beer, and then, accompanied by two treasury agents, moved to its parking spot to await 12:01 a.m. April 7, 1933.”

Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection

“When the night was done, one executive for the brewery reported they had a stack of money 18 inches high, and when they counted all the night’s receipts they found they had taken in over one quarter of a million dollars for their beer,” according to RustyCans.com, adding, “Things were so chaotic that they got payments for beer they didn’t even remember selling. Of course, the fact that Harlow [a heavy drinker], stuck around partying with the brewery employees probably didn’t help!”

Courtesy of CemeteryGuide.com

Zobelein was doing his best to quench the thirst of LA, and the region. City population was about 1.3 million — more than twice what it was when Prohibition began. But with Los Angeles down to a single brewery, there were not enough suds to go around in the months between April and when Prohibition was repealed, so Eastside had its work cut out for it.

Under the headline “Shortage of Beer in Los Angeles,” the June 1933 issue of The American Brewer reported: “An acute shortage of beer is being experienced at Los Angeles, where but one brewery is in operation. Retailers there are willing to pay as high as $6 a case for beer that sells in San Francisco for $2.40. Out of the State brewers are finding the Los Angeles field a splendid market and beer is coming in from Mexico, Japan and Canada, as well as from Europe, despite the high duty.”

Courtesy of Skyscraperpage.com

Los Angeles/Eastside Brewery continued successfully through the 1930s, producing Eastside Lager Beer (which remained its best seller), Eastside Ale, Eastside Bock and Luxury Extra Dry Pilsner, among others, including Brown Derby Beer (named for the LA landmark) for Safeway stores. Eastside was bought by Milwaukee’s Pabst Brewing — the first of the big breweries to expand to the West Coast — in 1948, but continued to operate as a separate company until 1953, when Pabst built a new brewery next door to produce its own beer. Eastside Lager was still brewed, but became a low-priced discount beer, and renamed Eastside Old Tap — which, appropriately, was sold at Dodger Stadium on its opening day in 1962.

Pabst continued brewing in Los Angeles until 1979, when it closed the facility and sold off the property. Fortunately, some of the structures of the original Los Angeles Brewery remain and, as previously mentioned, is now the Brewery Arts Complex. Fittingly, carrying on the beer legacy of that property over 120 years later is the restaurant and expertly curated beer bar, Barbara’s at the Brewery. Unfortunately, Barbara’s had to close this past December, and is trying to raise money to reopen. If you’d like to help bring back Barbara’s at the Brewery, please visit this link: gofund.me/c9c8e6ca

Celebrate National Beer Day!

Since we can’t toast the holiday at Barbara’s, why not pay homage to LA’s brewing history by visiting one of SoCal’s many craft breweries to drink/eat onsite, or drop by to pick up some beer to go if you’re not ready to visit establishments quite yet.

And if you’re staying in, there is an old movie that would make the perfect film to watch on National Beer Day. Only 65 minutes long, What! No Beer? is a screwball comedy starring an aging Buster Keaton and a young Jimmy Durante as two guys who get the idea of opening a brewery just before beer is legalized after Prohibition, in order to get rich when it does. Released in theatres February 10, 1933, its timing couldn’t have been better, despite the fact that MGM studio and the filmmakers at the time had no idea that two months after that date, 4.0% abv beer would become legal — which may explain why it was a box office hit when it opened.

Filmed around LA at the time, it includes some great shots on Silverlake streets, including multiple beer barrels rolling down a steep hill chasing Keaton and disturbing “traffic” (such as it was in the early 1930s), as well as scenes at Echo Park Lake. Hilarity, hi-jinks and slapstick “brewing” scenes ensue, along with some pre-Hollywood Production Code sexiness. The film can be rented or purchased through Amazon Prime or YouTube.

In Wishful Drinking, Tomm Carroll opines and editorializes on trends, issues and general perceptions of the local craft beer movement and industry, as well as beer history. Feel free to let him know what you think (and drink); send comments, criticisms, kudos and even questions to beerscribe@earthlink.net.